Lambert: The previous isn’t lifeless….

By Pauline Grosjean, Professor, Faculty of Economics, UNSW. Initially printed at VoxEU.

The implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine will outlast the battle itself. Battle has enduring penalties on financial, social, and political outcomes. The results on people and households are equally persistent, and stay over generations (Blattman and Miguel 2010, Bauer et al. 2014, Grosjean 2014, Couttenier et al. 2019).

In a chapter of the VoxEU eBook on The Economics of the Second World Battle printed in 2019, I mentioned the lengthy shadow of victimisation in WWII on political belief and social preferences. I targeted on the political and social norms which can be most crucial for long-run financial development and political stability. For instance, belief in formal establishments is a key determinant of financial development (Acemoglu 2005, Acemoglu et al. 2011, Besley and Persson 2009, 2010), market improvement (Greif 2012), financial liberalisation (Grosjean and Senik 2011), and post-conflict political restoration (Bigombe et al. 2000). Belief in others and social cohesion are additionally essential elements in development (Knack and Keefer 1997, Guiso et al. 2010), the functioning of markets (Fafchamps 2006) and institutional high quality (Tabellini 2008, 2010).

A consultant pattern of respondents throughout 35 nations surveyed in 2010, 65 years after the top of the battle, exhibits {that a} household historical past of wartime victimisation has systematically eroded political belief and the perceived legitimacy of establishments (Grosjean 2014, Grosjean 2019). Belief in authorities establishments is strongly and negatively related to a household historical past of wartime victimisation. The impact is analogous on perceived equity of the courts. These results maintain whatever the battle’s end result for the nation, are persistent throughout generations – results are nonetheless discovered among the many grandchildren of these immediately affected by the battle – and are giant in magnitude. At present, individuals whose households have been victimised within the battle are much less trusting of the central state and of the courts by 0.07 and 0.08 commonplace deviations, in contrast with others with comparable socioeconomic traits in the identical locality. For belief within the central state, that is almost 5 instances the impact of being unemployed; for belief within the courts, it’s ten instances.

Larger publicity to violence has additionally made individuals extra more likely to have interaction in political and social teams and in collective motion by, for instance, demonstrating, hanging, or signing petitions. Once more, the destiny of the nation on the battle’s finish has no robust affect and the impact is multigenerational.

What does such involvement in collective motion and in social and political teams seize? The sociological literature is split. Putnam (1995) sees it as selling social cohesion. Bourdieu (1985) noticed the other: social capital could be exploited in group rivalry, resulting in social exclusion and political violence (see additionally Portes 1998). Not too long ago the “darkish aspect” of social capital has been unveiled by Satyanath et al. (2013): the density of civic associations in interwar Germany helped advance the Nazi Occasion to energy. Equally, victims of the Nineties Tajik civil battle take part extra in teams after they have much less belief in different individuals and the state (Cassar et al. 2013a, b).

Within the case of these whose households have been victimised in WWII, the proof means that collective motion spurred by this victimisation could also be equally darkish in nature. In households that have been victimised, individuals who take part in teams at present are those who place much less belief in others in addition to in politics (Grosjean 2014: 447-448).

General, this analysis highlights the unfavourable and enduring results of victimisation on political belief and on social cohesion, essential determinants of long-run stability and society.

Completely different Histories of Wartime Victimisation

My earlier analyses purposefully abstracted away from doable macro-level results of battle on the standard of political establishments and on social capital. Counting on the Life in Transition Survey (LITS), a nationally consultant survey carried out in 2010 in additional than 30 nations of former Communist Europe and Central Asia, in addition to a handful of Western nations, I in contrast reported institutional belief and social capital proxies by people from the identical city, a few of whom reported victimisation of their household and others not. The victimisation query requested whether or not the respondent, their mother and father or their grandparents have been bodily injured or killed throughout WWII. By specializing in individuals in the identical city, a fortiori in the identical nation, I used to be capable of evaluate the attitudes of people who confronted the identical establishments and to minimise the affect of different elements, reminiscent of cultural norms, that would confound the connection of curiosity.

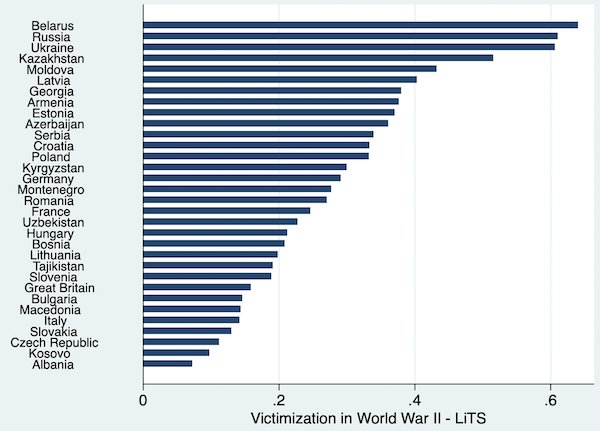

But, there’s additionally nice variability within the extent of victimisation throughout WWII throughout Europe, and such cross-country variation could also be instructive. The previous USSR suffered the best loss in human life, with 7.5 million reported battle deaths (Sarkees and Wayman 2010) and whole deaths (civilian and army) within the 26-27 million vary (Ellman and Maksudov 1994). household victimisation reported in 2010, three successor states to the USSR stand out: Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine (Panel B of Determine 1). 64% of surveyed respondents in Belarus report having had a member of the family killed or injured because of WWII, 61% in Russia and 60% in Ukraine.

Determine 1 Historical past of household victimisation in WWII

Notes: The determine plots the share of respondents at nation stage who reply sure to the next query: “Have been you, your mother and father or any of your grandparents bodily injured or killed in the course of the Second World Battle?” On the nation stage, the frequency of self-reported victimisation is extremely correlated with unbiased measures of war-related fatalities, even adjusting for the evolution of potential publicity throughout generations (Grosjean 2014: 436).

Supply: Life in Transition Survey, 2010.

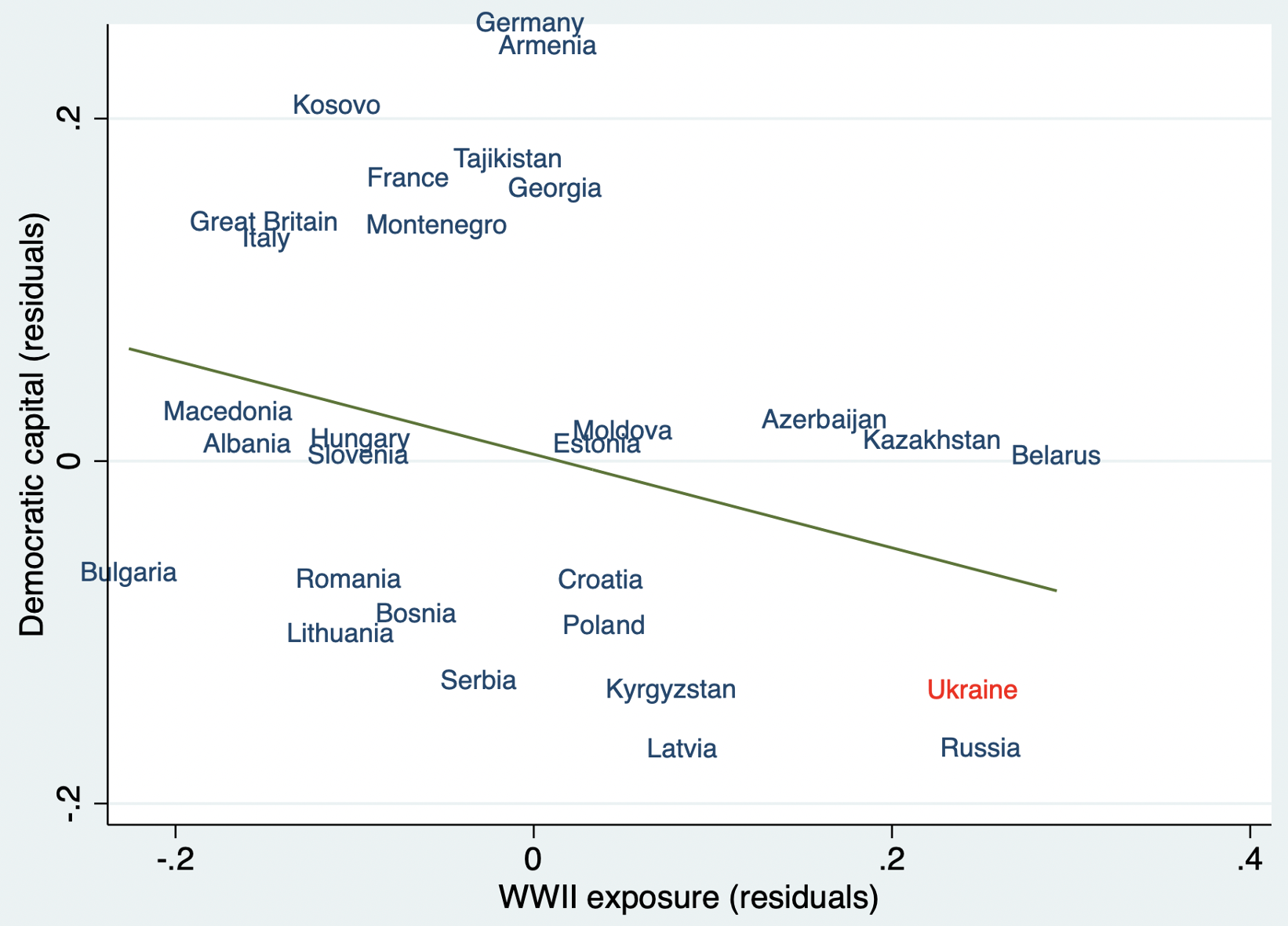

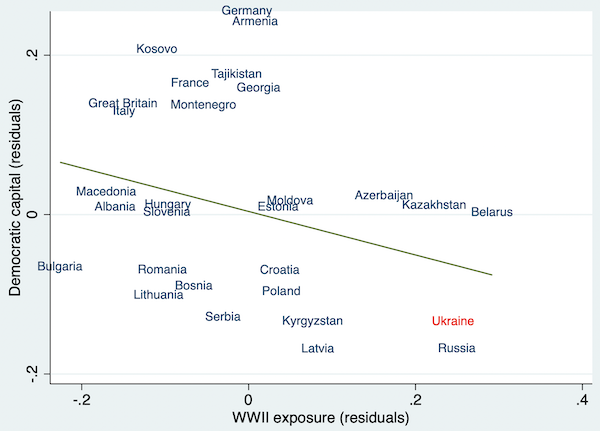

Alongside this excessive victimisation, Ukraine can be among the many nations that scored lowest on political belief in 2010 in contrast with the remainder of the pattern (normalised measure2 of political belief: -0.39, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0.018, P-value distinction in means <0.001, with solely Romania and Uzbekistan scoring decrease within the pattern) and highest on our measures of membership in teams (normalised measure: -0.21, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: -0.01, P-value distinction in means <0.001). Ukraine was additionally among the many nations the place assist for democracy, or democratic capital, was lowest, as illustrated in Determine 2. On common, respondents in Ukraine agreed lower than the pattern common with the assertion that “a democracy is one of the best political system” (normalised measure: -0.30, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0,01, P-value distinction in means <0.001).

Admittedly, the state of affairs in Ukraine in 2010 was very totally different from what it was ten years later. However the aspirations that the 2014 Maidan Revolution embodied and the progress achieved since then, Ukraine was nonetheless, within the 2016 wave of the Life in Transition Survey, among the many nations with the bottom belief in central establishments (normalised measure: -0.63, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0.02, P-value distinction in means <0.001) and the bottom common assist for democracy (normalised measure: -0.22, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0.01, P-value distinction in means <0.001).

Determine 2 Cross-country relationship between democratic capital and household historical past of victimisation in WWII

Notes: This determine plots the residuals of a cross-country regression of assist for a democratic system (share of respondents who agree with the next assertion: a Democracy is one of the best political system) in opposition to the residuals of a regression of household publicity to WWII (horizontal axes), controlling for particular person traits (age, age squared, gender, schooling, working standing, family dimension, faith, mom tongue). Commonplace errors are adjusted for clustering on the nation stage.

Ukraine: On the Confluence of Enduring Historic Legacies

The literature has additionally documented the enduring affect of pre-WWI empires of Central and Japanese Europe on political and social belief (Grosjean 2011a), financial establishments and improvement (Grosjean 2011b), corruption (Becker et al. 2016), and attitudes in the direction of democracy (Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya 2015).

Many present-day nations of Central and Japanese Europe had at one time been divided between a number of empires, with many borders of present-day nations the results of generally arbitrary army advances and peace treaties. Poland, for instance, had been divided amongst three empires – Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Prussia – for over a century till 1918 (Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya 2015) and its borders redrawn after WWII (Becker et al. 2020). Fashionable-day Ukraine had been divided between Russia and Austria-Hungary, whereas components of Ukraine had additionally been underneath Ottoman rule till the top of the 18th century.

Becker et al. (2016) doc constructive results of Habsburg rule on political belief within the pattern of nations that have been divided between the Habsburg and one other empire (Poland, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, Montenegro). Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya (2015) spotlight a permanent increased desire for democracy in components of Poland that have been underneath Austrian rule in comparison with these underneath Russian rule, though they discover no distinction between components that have been dominated by Russia versus Prussia. Wanting extra particularly at Ukraine appears to level to comparable outcomes. Political belief and democratic capital, measured in 2010, have been 0.26 and 0.21 commonplace deviations decrease within the previously Russian components in comparison with components dominated by Austria-Hungary. That is the case even after controlling for potential variations in non secular affiliation, mom tongue, earnings, or schooling.

Conclusion

Ukraine on the daybreak of the twenty first century stood on the confluence of putting up with legacies of a divided and violent previous. It had been divided between a number of empires on the eve of WWI and skilled among the many highest ranges of victimisation within the twentieth century in Europe and the previous USSR (Snyder 2011). Some authors have warned of battle traps (Collier 2003), during which the unfavourable penalties of 1 battle present the seeds for additional devastation. This column illustrates the potential for such a entice by exhibiting the unfavourable and enduring results of victimisation on political belief, social cohesion, and democratic capital. However Ukraine can be the sufferer of one other entice: former empires not solely affect political preferences, but additionally immediately trigger political instability and battle when rulers politicise the dream of recreating them. Border areas of former empires are dangerous locations. And given the historical past of imperial border modifications in Europe, few locations are resistant to this threat.

Writer’s be aware: I thank Alice Calder and Federico Masera for insightful feedback.

By Pauline Grosjean, Professor, Faculty of Economics, UNSW. Initially printed at VoxEU.

Battle durably shapes how people view the state and work together with one another. This column makes use of knowledge from greater than 35,000 people in 35 nations to point out how battle victimisation in WWII left a unfavourable imprint on ranges of political belief all through Europe and Central Asia that has persevered over generations. The writer additionally finds a long-lasting influence of pre-WWI empires on political belief and democratic capital that varies even throughout areas which have since been built-in into the identical nation. The findings have implications for Ukraine, a rustic that skilled each a divided historical past and among the highest victimisation charges in WWII.

The implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine will outlast the battle itself. Battle has enduring penalties on financial, social, and political outcomes. The results on people and households are equally persistent, and stay over generations (Blattman and Miguel 2010, Bauer et al. 2014, Grosjean 2014, Couttenier et al. 2019).

In a chapter of the VoxEU eBook on The Economics of the Second World Battle printed in 2019, I mentioned the lengthy shadow of victimisation in WWII on political belief and social preferences. I targeted on the political and social norms which can be most crucial for long-run financial development and political stability. For instance, belief in formal establishments is a key determinant of financial development (Acemoglu 2005, Acemoglu et al. 2011, Besley and Persson 2009, 2010), market improvement (Greif 2012), financial liberalisation (Grosjean and Senik 2011), and post-conflict political restoration (Bigombe et al. 2000). Belief in others and social cohesion are additionally essential elements in development (Knack and Keefer 1997, Guiso et al. 2010), the functioning of markets (Fafchamps 2006) and institutional high quality (Tabellini 2008, 2010).

A consultant pattern of respondents throughout 35 nations surveyed in 2010, 65 years after the top of the battle, exhibits {that a} household historical past of wartime victimisation has systematically eroded political belief and the perceived legitimacy of establishments (Grosjean 2014, Grosjean 2019). Belief in authorities establishments is strongly and negatively related to a household historical past of wartime victimisation. The impact is analogous on perceived equity of the courts. These results maintain whatever the battle’s end result for the nation, are persistent throughout generations – results are nonetheless discovered among the many grandchildren of these immediately affected by the battle – and are giant in magnitude. At present, individuals whose households have been victimised within the battle are much less trusting of the central state and of the courts by 0.07 and 0.08 commonplace deviations, in contrast with others with comparable socioeconomic traits in the identical locality. For belief within the central state, that is almost 5 instances the impact of being unemployed; for belief within the courts, it’s ten instances.

Larger publicity to violence has additionally made individuals extra more likely to have interaction in political and social teams and in collective motion by, for instance, demonstrating, hanging, or signing petitions. Once more, the destiny of the nation on the battle’s finish has no robust affect and the impact is multigenerational.

What does such involvement in collective motion and in social and political teams seize? The sociological literature is split. Putnam (1995) sees it as selling social cohesion. Bourdieu (1985) noticed the other: social capital could be exploited in group rivalry, resulting in social exclusion and political violence (see additionally Portes 1998). Not too long ago the “darkish aspect” of social capital has been unveiled by Satyanath et al. (2013): the density of civic associations in interwar Germany helped advance the Nazi Occasion to energy. Equally, victims of the Nineties Tajik civil battle take part extra in teams after they have much less belief in different individuals and the state (Cassar et al. 2013a, b).

Within the case of these whose households have been victimised in WWII, the proof means that collective motion spurred by this victimisation could also be equally darkish in nature. In households that have been victimised, individuals who take part in teams at present are those who place much less belief in others in addition to in politics (Grosjean 2014: 447-448).

General, this analysis highlights the unfavourable and enduring results of victimisation on political belief and on social cohesion, essential determinants of long-run stability and society.

Completely different Histories of Wartime Victimisation

My earlier analyses purposefully abstracted away from doable macro-level results of battle on the standard of political establishments and on social capital. Counting on the Life in Transition Survey (LITS), a nationally consultant survey carried out in 2010 in additional than 30 nations of former Communist Europe and Central Asia, in addition to a handful of Western nations, I in contrast reported institutional belief and social capital proxies by people from the identical city, a few of whom reported victimisation of their household and others not. The victimisation query requested whether or not the respondent, their mother and father or their grandparents have been bodily injured or killed throughout WWII. By specializing in individuals in the identical city, a fortiori in the identical nation, I used to be capable of evaluate the attitudes of people who confronted the identical establishments and to minimise the affect of different elements, reminiscent of cultural norms, that would confound the connection of curiosity.

But, there’s additionally nice variability within the extent of victimisation throughout WWII throughout Europe, and such cross-country variation could also be instructive. The previous USSR suffered the best loss in human life, with 7.5 million reported battle deaths (Sarkees and Wayman 2010) and whole deaths (civilian and army) within the 26-27 million vary (Ellman and Maksudov 1994). household victimisation reported in 2010, three successor states to the USSR stand out: Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine (Panel B of Determine 1). 64% of surveyed respondents in Belarus report having had a member of the family killed or injured because of WWII, 61% in Russia and 60% in Ukraine.

Determine 1 Historical past of household victimisation in WWII

Notes: The determine plots the share of respondents at nation stage who reply sure to the next query: “Have been you, your mother and father or any of your grandparents bodily injured or killed in the course of the Second World Battle?” On the nation stage, the frequency of self-reported victimisation is extremely correlated with unbiased measures of war-related fatalities, even adjusting for the evolution of potential publicity throughout generations (Grosjean 2014: 436).

Supply: Life in Transition Survey, 2010.

Alongside this excessive victimisation, Ukraine can be among the many nations that scored lowest on political belief in 2010 in contrast with the remainder of the pattern (normalised measure2 of political belief: -0.39, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0.018, P-value distinction in means <0.001, with solely Romania and Uzbekistan scoring decrease within the pattern) and highest on our measures of membership in teams (normalised measure: -0.21, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: -0.01, P-value distinction in means <0.001). Ukraine was additionally among the many nations the place assist for democracy, or democratic capital, was lowest, as illustrated in Determine 2. On common, respondents in Ukraine agreed lower than the pattern common with the assertion that “a democracy is one of the best political system” (normalised measure: -0.30, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0,01, P-value distinction in means <0.001).

Admittedly, the state of affairs in Ukraine in 2010 was very totally different from what it was ten years later. However the aspirations that the 2014 Maidan Revolution embodied and the progress achieved since then, Ukraine was nonetheless, within the 2016 wave of the Life in Transition Survey, among the many nations with the bottom belief in central establishments (normalised measure: -0.63, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0.02, P-value distinction in means <0.001) and the bottom common assist for democracy (normalised measure: -0.22, pattern common outdoors Ukraine: 0.01, P-value distinction in means <0.001).

Determine 2 Cross-country relationship between democratic capital and household historical past of victimisation in WWII

Notes: This determine plots the residuals of a cross-country regression of assist for a democratic system (share of respondents who agree with the next assertion: a Democracy is one of the best political system) in opposition to the residuals of a regression of household publicity to WWII (horizontal axes), controlling for particular person traits (age, age squared, gender, schooling, working standing, family dimension, faith, mom tongue). Commonplace errors are adjusted for clustering on the nation stage.

Ukraine: On the Confluence of Enduring Historic Legacies

The literature has additionally documented the enduring affect of pre-WWI empires of Central and Japanese Europe on political and social belief (Grosjean 2011a), financial establishments and improvement (Grosjean 2011b), corruption (Becker et al. 2016), and attitudes in the direction of democracy (Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya 2015).

Many present-day nations of Central and Japanese Europe had at one time been divided between a number of empires, with many borders of present-day nations the results of generally arbitrary army advances and peace treaties. Poland, for instance, had been divided amongst three empires – Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Prussia – for over a century till 1918 (Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya 2015) and its borders redrawn after WWII (Becker et al. 2020). Fashionable-day Ukraine had been divided between Russia and Austria-Hungary, whereas components of Ukraine had additionally been underneath Ottoman rule till the top of the 18th century.

Becker et al. (2016) doc constructive results of Habsburg rule on political belief within the pattern of nations that have been divided between the Habsburg and one other empire (Poland, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, Montenegro). Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya (2015) spotlight a permanent increased desire for democracy in components of Poland that have been underneath Austrian rule in comparison with these underneath Russian rule, though they discover no distinction between components that have been dominated by Russia versus Prussia. Wanting extra particularly at Ukraine appears to level to comparable outcomes. Political belief and democratic capital, measured in 2010, have been 0.26 and 0.21 commonplace deviations decrease within the previously Russian components in comparison with components dominated by Austria-Hungary. That is the case even after controlling for potential variations in non secular affiliation, mom tongue, earnings, or schooling.

Conclusion

Ukraine on the daybreak of the twenty first century stood on the confluence of putting up with legacies of a divided and violent previous. It had been divided between a number of empires on the eve of WWI and skilled among the many highest ranges of victimisation within the twentieth century in Europe and the previous USSR (Snyder 2011). Some authors have warned of battle traps (Collier 2003), during which the unfavourable penalties of 1 battle present the seeds for additional devastation. This column illustrates the potential for such a entice by exhibiting the unfavourable and enduring results of victimisation on political belief, social cohesion, and democratic capital. However Ukraine can be the sufferer of one other entice: former empires not solely affect political preferences, but additionally immediately trigger political instability and battle when rulers politicise the dream of recreating them. Border areas of former empires are dangerous locations. And given the historical past of imperial border modifications in Europe, few locations are resistant to this threat.

Writer’s be aware: I thank Alice Calder and Federico Masera for insightful feedback.

References accessible on the unique.