By Lambert Strether of Corrente

CDC, and the public health establishment generally, promote a paradigm of “personal risk assessment” that will enable you to “live with” Covid. Implicit in that social contract is that CDC will provide the necessary data for you to make the assessment; obviously, an individual isn’t going to be personally tracking case counts, or new variants, or dipping into their local wastewater to run tests. Leaving aside the viciously neoliberal and eugenic[1] character of the paradigm, CDC is also failing to uphold its end of the bargain (and not for the first time).

In this post, I’ll examine CDC’s latest betrayal: Its failure to alert the public to a rapidly doubling new variant, BQ.1.* (BQ.1.* includes both BQ.1 and BQ.1.1.) First, I’ll establish that BQ.1.* is a variant that you should be concerned about. Next, I’ll look at the timeline that shows CDC’s failure to warn. Next, I will do a post mortem on whether CDC’s latest betrayal is attribute to persons (“malevolence”) or institutions (“operational incapacity”). Finally, I’ll look into CDC’s operational incapacity more deeply.

The Danger

BQ.1.* is a dangerous variant. It is characterized by rapid doubling time. From Reuters:

U.S. health regulators on Friday estimated that BQ.1 and closely related BQ.1.1 accounted for 16.6% of coronavirus variants in the country, , while Europe expects them to become the dominant variants in a month.

“These variants (BQ.1 and BQ.1.1) can quite possibly lead to a very bad surge of illness this winter in the U.S. as it’s already starting to happen in Europe and the UK,” said Gregory Poland, a virologist and vaccine researcher at Mayo Clinic.

Here is a chart that shows doubling time since the beginning of the pandemic:

As you can see, even a week is a long time when the virus is getting rolling. To be fair, the United States population is not the same population it was in 2020, when Covid first hit: Many more people have acquired immunity, many more are vaxed, most have different combinations of immunity and vaccination, and so on; we are no longer, as it were, virgin territory. Which makes BQ.1.*’s next characteristic all the more important–

BQ.1.* is immune evasive (that is, previous infection does not protect from a second infection). From Fortune:

BQ.1.1 is thought to be the most immune-evasive new variant, according to Dr. Eric Topol, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research and founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute.

BQ.1.1’s extreme immune evasiveness “sets it up to be the principal driver of the next U.S. wave in the weeks ahead,” Topol tweeted Friday.

On Thursday, he told Fortune that scientists won’t know to what extent it challenges vaccines, if it does, until it reaches 30%-50% of cases somewhere.

“It’s not going to wipe out vaccine efficacy, but it could but a dent in protection against hospitalizations and death,” he said.

(Wait. Since vaccines don’t prevent transmission, I thought protection against “hospitalizations and death” was the reason to het them?

Next, BQ.1.* renders some treatments obsolete. Fortune again:

BQ.1.1 is already known to escape antibody immunity, rendering useless monoclonal antibody treatments used in high-risk individuals with COVID. According to a study last month out of Peking University’s Biomedical Pioneering Innovation Center in China, BQ.1.1 escapes immunity from Bebtelovimab, the last monoclonal antibody drug effective on all variants, as well as Evusheld, which works on some. Along with variants CA.1 and XBB, BQ.1.1 could lead to more severe symptoms, the authors wrote.

Finally, New York City is under the gun. From Becker’s Hospital Review:

Health experts are carefully watching COVID-19 trends in New York amid signs the nation will face a winter surge. The state has seen an increase in hospitalizations over the last month.

Statewide, the daily average for COVID-19 hospitalizations is up 15 percent over the last two weeks, according to HHS data compiled by The New York Times. As of Oct. 20, an average of 3,095 people were hospitalized in New York. On Oct. 2, that figure was 2,614.

The increase in hospitalization rates comes as a pair of omicron relatives dubbed “escape variants” gain prevalence nationwide. The strains — BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 — are most prevalent in New York and New Jersey, where they account for nearly 30 percent of new infections, according to CDC estimates for the week ending Oct. 22. BQ.1’s rising prevalence may be driving the jump in hospitalizations, but scientists say it’s still too early to confirm a causal relationship.

While hospitalizations appear to be trending upward in New York, cases have remained relatively flat throughout the month. This discrepancy highlights the difficulty of monitoring virus activity in an era of unreliable case data and a departure from daily reporting cadences.

(Ya think? How’d that happen?)

For those of us who remember the very first Covid wave in 2020, this is worrisome. From Fortune:

New York is when it comes to COVID forecasting for a couple of reasons: its volume of incoming international travelers, and its robust capabilities to genetically sequence COVID virus samples, experts say.

When a variant gains traction in Europe, as the BQ family has, trackers like Rajnarayanan and Gregory know to look for it in the U.S. The first place they check: New York.

Together, Omicron spawn BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 are “following the same script” as other previously dominant variants—like the original strain of COVID, Delta, and the original strain of Omicron—by , fellow variant tracker Dr. Ryan Gregory, a professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, told Fortune.

(Well, if the spread follows the pattern of 2020, the first places to track are the Hamptons and the Hudson Valley, as those who can leave, leave.)

If I am to make a personal risk assessment about flying into New York — as indeed many PMC, flying (unmasked) on planes, or attending (unmasked) conferences will do — I really need to know that a dangerous variant is exhibiting doubling behavior there. And I need to now it now, ASAP, because the variant’s doubling behavior means a week, let alone two weeks, is far too long. Unfortunately for many, CDC failed to give timely warning. Let’s look at why..

The Timeline

Here is the timeline for CDC’s “reveal” of BQ.1.*.[2] From Fierce Healthcare (and kudos to them for explaining so clearly a story that has yet to appear in [genuflects] the Times or the Post):

The highly infectious and evasive BQ.1.1 variant not only has a foothold in the U.S., it may have established that foothold weeks ago. The data on the variant have prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to redo previous weeks’ variants tracking charts.

“It’s been ,” Kevin Kavanagh, M.D., founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA, told Fierce Healthcare.

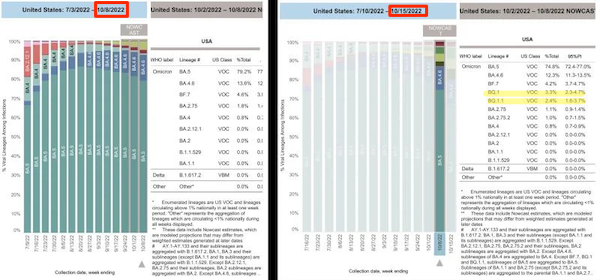

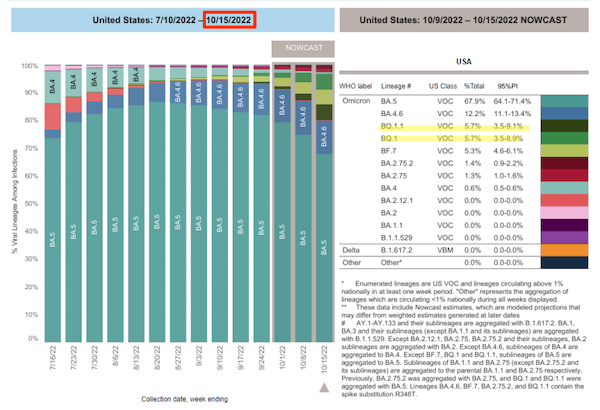

The charts below tell the story. The left shows the first version of CDC tracking data for the week ending Oct. 8, where BQ.1.1 (and its cousin, BQ.1) don’t even appear. The CDC had grouped those data under the BA.5 label, which has been the most dominant subvariant of omicron since early July.

After examining additional data, the CDC this week reconfigured the chart to show BQ 1.1. accounting for 2.4% of new cases of COVID-19 for the week ending Oct. 8 and BQ.1 accounting for 3.3%.

Now look at the chart for the week ending Oct. 15. Both variants now account for 5.7% of new COVID-19 cases in the U.S.

Kavanagh said BQ.1.1 “appears to be doubling every week. Data from CDC appears delayed in being posted on this variant. Once it became apparent in the last few weeks that the variant is having a significant impact, the data were separated.”

So, the doubling behavior of BQ.1.* was hidden by being aggregated with the declining BA.5’s data. At some point after October 8, CDC disaggregated them, and BQ.1.* became visible. Being as charitable as possible to CDC, it got the data out a week late (October 15, not October 8), but as I point out above, a week is too slow. If one wishes not to be charitable, CDC’s internal deliberations took far too long (“it became apparent in the last few weeks”). How did this happen?

The Post Mortem

There are at least to reasons CDC failed to warn the public about BQ.1* in a timely fashion: Malevolence, and operational incapacity.

Taking malevolence first, from WSWS:

On Friday, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its variant monitoring graphs to show that the highly contagious and immune-evasive descendants of the Omicron BA.5 subvariant, known as BQ.1 and BQ.1.1, now account for a combined 11.4 percent of all sequenced variants.

However, the “update” epidemiologist Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding tweeted these same data, which he noted were leaked to him from a “CDC-insider source” which informed him that the CDC had been regarding the state of the variants in the US. Feigl-Ding’s tweet went viral, garnering over 10,000 likes and over 5,000 retweets within hours, the publicly.

This is among the most significant by the foremost health agency in the US since the start of the pandemic. that the CDC deliberately concealed this vital information from the public for weeks, as part of the relentless propaganda campaign by the Biden administration and the corporate media to falsely claim that “the pandemic is over.”

Well, CDC data drops every Friday, at a stately once-a-week pace. Readers know, I am sure, that I hold no brief for the CDC. However, there’s a good deal of handwaving in WSWS’s post, which I have helpfully underlined; sequence and causality are not the same. In particular, I doubt very much that a Tweetstorm can cause CDC to do anything. If it could, Rochelle Walensky — bless her heart — would be recommending masking because #CovidIsAirborne. I also note that WSWS seems to have no knowledge of how CDC variant data is actually collected.

That brings us to operational incapacity. Reporter Alexander Tin found a transcript of CDC giving its version at a webinar with testing labs on October 17:

NATALIE THORNBURG, CDC [00:22:55] And then last week, we had an update where we added three additional sublineages [including the two BQ.1.* lineages] to the data tracker.

And just a reminder, when we decide the reason we decide to break things out, sublineages out on the data tracker, we have a couple of criteria. One, it has to reach at least 1% prevalence nationally. Two, it has to have medically relevant substitutions. So it has to have substitutions that could show a reduction in neutralization titers, have some effect on– we haven’t really seen diagnostics, but have some effect on diagnostics or therapeutics. But what we’ve really seen most– most often is substitutions that could affect neutralization. And then of course, we need a method for identifying those sublineages.

, as well as BA.2.75.2

So CDC’s defense is that they did not have the operational capacity to disaggregate BQ.1.* until they got the data from Pango[lin][4], at the usual stately every Friday pace. the Hence the following subtweet directed at Eric Fiegel-Ding:

Virtually all of the underlying seq data are available to the public, and emerging variants are quickly flagged and discussed on scientific forums (& by experts / citizen scientists on Twitter)!

This conspiratorial, clout-chasing nonsense is dangerous and a disservice to us all.

— Duncan MacCannell (@dmaccannell) October 14, 2022

Personally, I lean toward the operational incapacity explanation, because it’s more stupid, and this is the stupidest timeline. Readers may differ! In any case and as usual, The Onion has the story covered: “We Have Coronavirus Under Control,’ Announces CDC Director As Nose Slowly Transforms Into Pangolin Snout” (from 3/05/20 (!!)). But what is Pangolin?

How Pangolin Shows CDC’s Operational Incapacity

Pangolin is a suite of open source software (lead developer; README):

Pangolin was developed to implement the dynamic nomenclature of SARS-CoV-2 lineages, known as the Pango nomenclature. It allows a user to assign a SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence the most likely lineage (Pango lineage) to SARS-CoV-2 query sequences.

It is available as a command line tool and a web application. The web application was developed by the Centre for Genomic Pathogen Surveillance. The command line tool is open source software available under the GNU General Public License v3.0.

(I am assuming that the WebApp somehow uses the command line tool on the backend, hence is GPL’ed, too. Pangolin includes a machine learning component, UShER, also GPLed).

Before going any further, let’s just ask the basic question: Why doesn’t CDC get the Pangolin volunteers some money so that they can speed up their work?! This every Friday drop just doesn’t make it, because the doubling capacity of the virus can outrun it.

Now let’s look at the instituional set-up for Pangolin (and please note that I have nothing but the utmost respect for the skills of the developers, or the power and beauty of their work). From MIT Technology Review:

[the Pangolin project is] a GitHub page staffed by around the world, led primarily by a PhD student in Scotland.

Those volunteers oversee a system called Pango, which has quietly become essential to global covid research. Its software tools and naming system have now helped scientists worldwide understand and classify nearly 2.5 million samples of the virus.

Researchers, public health officers, and journalists around the world use Pango to understand covid’s evolution. But few realize that .

Many of the foundational tools for tracking covid genomes have been developed and maintained by early-career scientists like O’Toole and Scher over the last year and a half. As the need for worldwide covid collaboration exploded, scientists rushed to support it with ad hoc infrastructure like Pango. Much of that work fell to tech-savvy young researchers in their 20s and 30s. They used informal networks and tools that were open source—meaning they were free to use, and anyone could volunteer to add tweaks and improvements.

“The people on the cutting edge of new technologies tend to be grad students and postdocs,” says Angie Hinrichs, a bioinformatician at UC Santa Cruz who joined the project earlier this year.

So, just to be clear, CDC has outsourced the essential technology for variant detection to volunteers[5]. (And what is the key characteristic of “grad students and postdocs”? They need to move on.) CDC has bet thousands of lives, perhaps tens or hundreds of thousands, on volunteers. Does that sound like a sensible approach to you? Why the heck, again, can’t CDC get them some kinda budget? What happens when the developer gets a better offer? Or moves to another institution? Do people at CDC think that complex open source software is maintained by little elves? Does this sound like operational capacity to you?[6]

Conclusion

I wouldn’t be so worried if CDC and the public health establishment hadn’t systematically ignored or discredited all forms of non-pharmaceutical intervention, and vax uptake was not at a standstill. But here are are: CDC delenda est. Burn the facilities, plow the rubble under, salt the earth. There’s no excuse for any of this.

NOTES

[1] The ability to assess personal risk is strongly correlated to income, which in turn is driven by class and “social determinants of health” generally. Yves’s helper Betty Jo, for example, who is dedicated to masking, ventilation, and Povidone iodine, won’t be running Bob Wachter’s complex risk assessment algorithm anytime soon; she’s too busy. Hence, stochastic eugenics.

[2] These screenshots have CDC’s NowCast algorithm on. I keep it off, because I don’t trust CDC’s models, based on experience. In some ways, NowCast makes CDC even more culpable; if you have model capable of predicting doubling behavior, why not reveal it?

[3] Here is the argument that CDC should have disaggregated the data much earlier, say on September 24:

2. “(…) with BQ.1 exceeding one percent of all sequenced variants on September 24 and BQ.1.1. reaching that threshold by the week of October 1. By the CDC’s rules, they have to break out these newer strains from all the ones being tracked and list their frequency.” pic.twitter.com/J1IvUy6CBt

— Nancy Delagrave | Covid-Stop (@RougeMatisse) October 17, 2022

However, we’d need more evidence that CDC was aware that BQ.1.* had passed the 1% threshold than a screenshot of the current chart, since CDC “backfills” the charts when new variants are disaggregated:

New CDC variant Nowcasts:

– BQ.1 and BQ 1.1 combined are now ~17% of new cases (up from 9.4% last week)

– BA 4.6 consistent from last week

– BA.5 is 62% of new cases (down from 70% last week)Note that CDC has always backfilled as sequences are received.https://t.co/xuOF2fkHPS pic.twitter.com/mYTDDbB32L

— Benjy Renton (@bhrenton) October 21, 2022

[4] The chart in this Tweet purports to show that CDC is slower than private labs:

This chart shows that the CDC is sitting on variant data for 2-3 weeks while state, university, and private labs are getting results and submitting them to a global database within 5-10 days.

The CDC has been sitting on these data for weeks. pic.twitter.com/vThbzVBUbZ

— Dr. Jorge Caballero stands with 🇺🇦 (@DataDrivenMD) October 14, 2022

But I can’t understand the chart, which is why it goes in a note. Readers?

[5] The Technology Review article is 2021, and that is the most recent version I can find. UShER, the GPLed Pangolin component, was run by volunteers in 2022.

[6] Maybe put the United States Digital Service on the case? Not to rewrite the code, but to straighten out the obvious oncoming trainwreck in getting Pangolin maintained? Without, please gawd, privatizing it in Big Pharma’s loving embrace?