By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“A forest ecology is a delicate one. If the forest perishes, its fauna may go with it. The Athshean word for world is also the word for forest.” ― Ursula K. Le Guin, The Word for World Is Forest

It’s been awhile since I’ve perambulated through the biosphere, but after the news flow this week (and the week before (and the week before that …)) I felt that I needed a palate cleanser. Perhaps you feel the same way. Here is an American Chestnut tree:

(Photography photo by Dr. Garden, Shutterstock.) I don’t know if this American Chestnut competes with Wukchumni’s Redwoods, but it’s certainly a wonderful tree. American Abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher wrote in “History of the American Chestnut” (1874):

[The American Chestnut’s] boughs are arranged with express reference to ease in climbing. Nature was in a good mood when the chestnut-tree came forth. It is, when well grown, a stately tree, wide-spreading, and of great size. Even in the forest the chestnut is a noble tree. But one never sees its full development except when it has grown in the open fields. It then assumes immense proportions. Having a tendency when cut down to send up many shoots from the stump, old trees are often found with four or five trunks springing from the same root. In such cases, no other American tree covers so wide a space of ground. Not even the oak attains to greater size or longevity.

A chestnut-tree in full bloom is a fine sight. It blossoms about the first of July, in clusters of long, yellowish-white filaments, like a tuft of coarse wool-rolls.

In Henry Ward Beecher’s time, the American Chestnut was a dominant species. From the American Chestnut Foundation (ACF):

The American chestnut, Castanea dentata, once dominated portions of the eastern U.S. forests. Numbering nearly four billion, the tree was among the largest, tallest, and fastest-growing in these forests. Because it could grow so rapidly and attain huge sizes, the American chestnut was often an outstanding feature in both urban and rural landscapes.

Chestnut wood was rot-resistant, straight-grained, and suitable for furniture, fencing, and building materials. In Colonial times, chestnut was preferred for log cabin foundations, fence posts, flooring, and caskets. Later, railroad ties and both telephone and telegraph poles were made from chestnut, many of which are still in use today.

Its nut fed billions, from insects to birds and mammals, and was a significant contributor to rural agricultural economies. Hogs and cattle were fattened for market by silvopasturing them in chestnut-dominated forests. Nut-ripening and gathering nearly coincided with the holiday season, and late 19th century newspapers often featured articles about railroad cars overflowing with chestnuts to be sold fresh or roasted in major cities.

(Castanea dentata, not the genus Aesculus (the horse chestnut), let alone the water chestnut.) In fact, the American Chestnut was a keystone species:

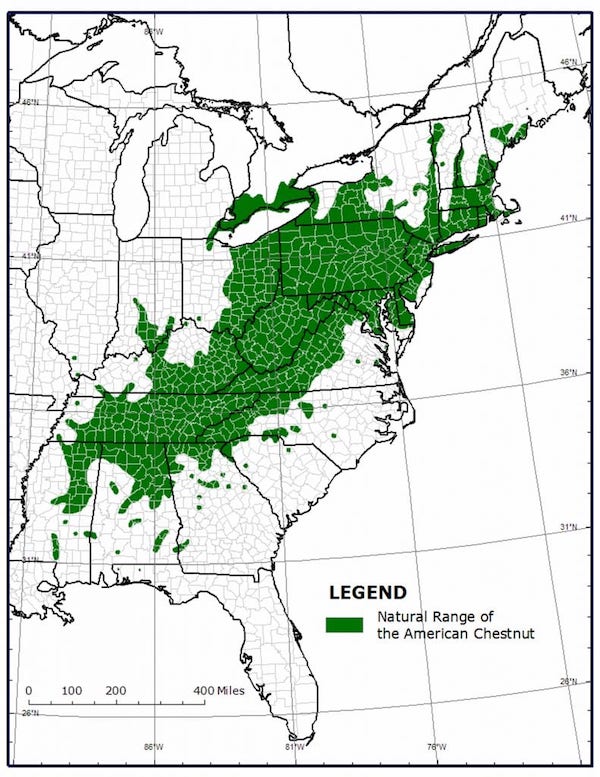

American Chestnuts supported many, many other species, ranging from 56 moth species whose caterpillars ate Chestnut leaves, to countless species of birds which relished their nuts, to large mammals such as black bears which relied upon the nuts as a main source of nourishment before hibernation. Over 200 million acres of forests were dominated by this tree, Castanae dentata.

So ignore the haters. Here is a range map, again from the ACF:

So what happened? What killed four billion trees? In a word, blight:

The year was 1904; the place the Bronx Zoological Park in New York City; the beginning of perhaps the greatest single natural catastrophe in the annals of forest history—the discovery of chestnut blight. In less than 50 years more than 80 percent of the American chestnut trees in the eastern hardwood forests were dead; the rest were dying. A tree species that once occupied an estimated 25 percent of the eastern forest, encompassing 200 million acres of forest land, was gone.

Here’s how the fungus did its work:

Chestnut Blight, a fungal disease caused by Cryphonectria parasitica… invades the bark through any wound to the tree. It will kill the cambium (a layer of tissue in the bark) in a circle all the way around the tree. This kills all living cells above the infection (a process known as girdling).

As the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service puts it:

The American chestnut has been reduced from a dominant overstory tree to a small understory shrub

“Shrub,” because as Henry Ward Beecher writes, the American Chestnut “send up many shoots from the stump,” or, in this case, the portion of the tree below the girdling. From the USDA:

[The] American chestnut has managed to exist as short-lived stump and root sprouts, which will occasionally live long enough to flower and bear fruit.

A tragic fall, for such a noble, generous tree.

Attempts to revive the American Chestnut gathered steam in the late 1970s, when the American Chestnut Symposium was held. The American Chestnut Foundation was founded in 1983, when it began its breeding program:

Breeding for blight resistance was initiated around 1930, but those early programs were abandoned as hopeless in the early 1960s because they had been unable to combine the forest competitiveness of American chestnut with the chosen sources of blight resistance, oriental chestnut species. However, the early breeding programs did identify species with blight resistance and develop methods for making crosses, cultivating seedlings, and screening them for blight resistance. Charles Burnham (1981) first hypothesized that the blight resistance of chestnut, C. mollissima Blume, could be backcrossed into American chestnut. Backcrossing is the method of choice for introgressing a simply inherited trait into an otherwise acceptable cultivar.

(We might call this approach “classical,” as opposed to “genetic engineering,” which we’ll get to in a moment.) Trees don’t breed as rapidly as fruit flies or even garden peas, and so 2019 – 1983 = 36 years after the ACF began its program, we are close to a result. From the USDA, “What it Takes to Bring Back the Near Mythical American Chestnut Trees“:

The American Chestnut Foundation, a partner in the Forest Service’s effort to restore the tree, is close to being able to make a blight-resistant American chestnut available. Several national forests in [the Northern and Southern research] regions have hosted experimental American chestnut plantings to assist in the development of reintroduction strategies…. The end goal of this collaboration among scientists and foresters is that the integration of their research will yield a holistic set of tools for reintroducing an iconic and long-absent tree species to the region and once again restore the lost giant of the eastern forests.

With typical American extravagance, we have a second foundation, the American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation:

Breeding for blight resistance is currently pursued by two separate foundations: the American Chestnut Foundation (ACF) is developing advanced hybrids, building on the work of earlier breeders to improve tree form while enhancing resistance; the American Chestnut Cooperators’ Foundation (ACCF) is not using Oriental genes for blight resistance, but intercrossing among American chestnuts selected for native resistance to the blight.

In the 1970’s, ACCF located American Chestnut survivors of the original blight epidemic and grafted them into ACCF plots for blight resistance testing.

ACCF intercrossed these and other chestnuts which our tests identified and planted the progeny in chestnut orchards (1982).

The ACCF is a volunteer (“cooperator”) organization of growers, with all the strengths and weaknesses that implies (and greatly in contrast to the ACF, whose Honorary Directors are Jimmy Carter and Norman Borlaug). From the ACCF’s current newsletter:

Projects and research by our founders began in the 60s, the roots of our heirloom program, built on the identification of existing blight-resistant all-American chestnut specimens and the examination of their blight-resistant qualities.

In 1985, the ACCF was organized and established to form the network of Cooperators dedicated to continuing pursuance of a research-based restoration program that serves this grand, native species….

With belief in the inherent strength of the American chestnut, the ACCF continues in its goal of restoring the American chestnut as a pure, significant species to its native range.

This is only accomplished by keeping a long-term perspective, continuing our work with patience and dedication, and through the continued efforts of our Cooperators.

(The ACCF’s website is purest 1990s, but includes a wealth of information on growing American Chestnuts.)

From the classical approach (whether based on Chinese crosses or All-American) we turn to genetic engineering, fruits (or nuts) of an effort at State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF). From the Washington Post, “Gene editing could revive a nearly lost tree. Not everyone is on board.”:

The fungus infecting chestnut trees thrives by secreting a chemical called oxalic acid, which kills cells and allows the pathogen to feast on the dead tissue. But many other plants, including bananas, strawberries and wheat, avoid that fate by producing an enzyme called oxalate oxidase that breaks down the toxin.

By 2014, [SUNY’s Bill] Powell and [Chuck] Maynard successfully added the wheat gene to chestnuts and were growing infection-resistant trees. The pair dubbed one line Darling 58, in honor of Herb [Darling, who initiated their project].

At the orchard in Syracuse this June, a team working with Andy Newhouse, a biologist and assistant director of the restoration project, had dug hooks into their tiny trunks to intentionally infect them with the fungus.

The results were dramatic: On the tree carrying the disease-resistant gene, a gray, dime-size sore swelled up at the site of the quarter-inch incision — an infection from which the tree would recover. “The big public policy question is: Should we bring back forests with genetically modified chestnut trees?” said Edward Messina, director of the Office of Pesticide Programs at the Environmental Protection Agency, one of the agencies weighing approval. “That’s a pretty heavy question.” “This case sits right at the intersection of cutting-edge science and public policy considerations,” [EPA’s Edward] Messina said in a video call. Still the question remains, he added: “Just because we can do something, should we?”

Good questions, which have now entered the regulatory process:

The EPA is reviewing how the transgenic tree’s enzyme will interact with people and the woodland environment. The Food and Drug Administration is evaluating the nuts’ nutritional safety. And the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service is reviewing how the tree may affect insects and other plants.

I think the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) review is the important one. From the Hill:

[T]he U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has just released a draft environmental impact statement [(EIS)] and draft plant pest risk assessment that will allow the unrestricted planting [“unregulated status”] of blight-tolerant GE chestnut trees on public and private lands. . Although the agency is recommending the tree’s release into wild forests, they are also requesting public input regarding their recent decision to do so. (You can submit comments here.)

45 days for public input over the holidays and ending December 27, seems less than ideal for such a big decision. Here are some of the concerns expressed in the previous round of public input:

APHIS solicited public comment for a period of 30 days ending September 7, 2021, as part of its scoping process to identify issues to address in the draft EIS. We received a total of 3,964 public comments. Issues most frequently cited in public comments on the notice concerning Darling 58 American chestnut included the following:

- Potential for gene flow to wild relatives;

- Potential to spread and become invasive;

- Potential non-target impacts, specifically to beneficial fungi, the microbiome, mycorrhizal networks, and the forest ecosystem;

- Potential impacts to wildlife, including pollinators, and threatened and endangered species; and

- Potential human health impacts from consuming nuts as well as potential allergies from pollen.

Of these, the first, “gene flow,” seems most important to me; if American Chestnut pollen is as promiscuous as alfalfa, that would be bad. The APHIS EIS argues that gene flow is both desirable and low risk. From “Environmental Impact Statements; Availability, etc.: State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry; Draft Plant Pest Risk Assessment for Determination of Nonregulated Status for Blight-Tolerant Darling 58 American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) Developed Using Genetic Engineering“:

American chestnut trees spread at an average rate of “no more than a few kilometers per century” (Paillet and Rutter 1989). It may take a century or more for blight tolerant chestnut trees to become dominant after the first pioneer trees become established in a given area. Slow natural colonization rates and frequent animal and pest pressure on seeds and seedlings (Clark et al. 2014), in addition with the limitations on pollen spread, suggest that chestnuts, regardless of type or transgene status, will not rapidly invade new areas (Cook and Forest 1978). Areas that are not intentionally planted with blight-tolerant chestnuts will likely remain without chestnuts for decades or longer (ESF 2019).

Under the Preferred Alternative [unregulated status], pollen mediated gene flow from Darling 58 American chestnut is possible. Darling 58 American chestnut is intended to be planted in proximity to native American chestnut trees with the hope that wild trees will flower and cross- pollinate to yield blight resistant seeds with the intention to increase the genetic diversity of the blight tolerant chestnuts. The transgenes from Darling 58 could also spread to related species through successful pollination with at least one transgenic parent.

There are two main objections to releasing the first genetically engineered plant “the purpose of spreading freely into the wild.” The first is the precautionary principle. From “That new chestnut? USDA plans to allow the release of GE trees into wild forest“:

Trees are complex organisms that interact with other living things over many growing seasons, if not centuries. For this reason, more research is needed if we are to fully understand the impact of GE chestnuts on larger forest ecosystems…. The supposition that genetically modified chestnut trees will behave in a specific and predictable way, based only on a decade of research, is premature, if not bad science.

Indeed, studies have shown that the genomic structure of transgenic plants can mutate as a result of gene insertion events and exhibit unexpected traits after reproducing. It is also possible that GE chestnuts, as they grow older and larger, will not be able to repel the blight, particularly if the OxO enzyme, produced by a wheat gene inserted into the DNA of the American chestnut, becomes less prevalent in mature trees. Scientists must be able to predict the future outcomes of their experiments and cannot reliably do so in the case of GE chestnuts.

However cliché it might be to state that those who do not learn the past are doomed to repeat it, in the case of the American chestnut this could very well be true. Chestnut restoration is an honorable undertaking, but the process should be done as carefully as possible, without harming the genomic heritage of this iconic tree. A wiser approach would be to adopt what the United Nations refers to as the “precautionary principle,” which restricts actions that can permanently harm a species or ecosystem, especially if there is no absolute certainty about their safety.

The second might be termed “the thin end of the wedge” or “the camel’s nose under the tent.” From In These Times:

The chestnut is very explicitly referred to in terms of its value for public relations and as a “test case.” Maud Hinchee, a former chief technology officer at tree biotechnology company ArborGen Inc. who had previously worked for Monsanto, stated, “We like to support projects that we think might not have commercial value but have huge value to society, like rescuing the chestnut. It allows the public to see the use of the technology and understand the benefits and risks in something they care about. Chestnuts are a noble cause.”

Scott Wallinger, a former vice president vice president of the paper corporation MeadWestvaco (now Westrock) said back in 2005, “This pathway [promoting the GE chestnut as forest restoration] can begin to provide the public with a much more personal sense of the value of forest biotechnology and .”

Even the American Chestnut Foundation said, “If SUNY ESF is successful in obtaining regulatory approval for its transgenic blight resistant American chestnut trees, then that would in the landscape.”

I have to say that when I wandered into this post, I didn’t expect to find an explosive issue of genetic engineering, where a smallish USDA agency was charged with setting an enormous precedent. But here we are.

It would be completely in character, sadly, for grant-driven university researchers to avoid the precautionary principle. It would also be completely in character for Monsanto, et al., to make a “noble cause” into a mere public relations effort for an enormous increase in GMOs (though I suppose eating transgenic plants would be better than eating bugs, as the WEF would like us to do). We’ve just had a collective experience — some might say an experiment without informed consent — with how capital manipulates genetic material: mRNA. Regardless of what one thinks of vaccination or mandates, it’s undeniable that the side effects of mRNA were not predicted or even tracked. “Unregulated status” means that will be true for Darling 58; and darling 58 is intended to mix with heirloom genes. That doesn’t seem like a good idea to me. Much as I’d love to see the American Chestnut restored to its orginal range, I don’t see what the rush is. Hasty, as Treebeard would say. If you want to comment on the APHIS EIS, here again is the link.

My preferences lie with the ACCH and its cooperator approach. A Utopian vision indeed!

Food for everyone that could last 1000 years. Every October everything stopping for nut gathering and festivals. November milling & processing. Something so secure about that in a way I don’t think someone from 2020 could understand.

— BUILD SOIL; Plant Chestnuts! (@BuildSoil) November 26, 2022

Robust, however. Jackpot-ready.