Simons, a Canadian fashion and home decor retailer, released a three-minute film in October showcasing the planned assisted death of a sick Canadian woman. The 37-year-old used Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) to die on Oct. 23 after dealing with complications from Ehlers Danlos syndrome, a group of inherited disorders that affect the connective tissue supporting many body parts.

While Simon’s tries to paint an uplifting picture of an individual’s decision to end their life in order to sell fashion and home decor, there are some serious questions about Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD), its intentions, and effects.

I’m certainly no expert on assisted death, and I don’t mean to question or attempt to judge which conditions warrant such assistance, but I would like to look at whether society has exhausted all other means of assistance to help provide a stable, fulfilling life before turning to assisted death.

So what exactly is MAiD? From Global News:

Enacted in 2016, Canada’s first MAiD legislation required that death be “reasonably foreseeable.” However, based on subsequent legal challenges, the legislation was ruled unconstitutional and the rules were changed. Starting last year, anyone who has a “serious and incurable illness, disease or disability” that is irreversible with “enduring and intolerable” suffering became eligible.

In theory there are safeguards: applications have to be approved by two doctors, the process takes at least 90 days, and those who cite inadequate financial and social support are not supposed to be approved.

Next year, the country is set to allow people to be killed exclusively for mental health reasons. It is also considering extending euthanasia to “mature” minors — children under 18 who meet the same requirements as adults.

Back to the woman featured in the Simons’ ad for a moment. She gave an interview to CTV News back in June describing how she wanted to live but couldn’t afford care to improve her quality of life.

This is what is at the heart of the debate in Canada. (Most US coverage of the program only mention financial issues in passing, like this Sept. 18 story from the New York Times titled “Is Choosing Death Too Easy in Canada?” It mentions “economic and housing challenges” exactly once at the end of the nineteenth paragraph.)

Both mental illness and disability are oftentimes inseparable from severe financial stress. There is evidence that poverty can cause or worsen mental illness, as well as physical ailments.

So we acknowledge that poverty is pain, but rather than relieving that pain, offer death, is that not just killing poor people?

Even if that isn’t the intent of MAiD, there is evidence it is having that effect. Again from Global News:

Critics say the government’s quick expansion of MAiD and insistence that it’s the compassionate thing to do misses an important factor. A massive number of Canadians with disabilities … are trapped in an excruciating cycle of poverty.

Only 31 percent of Canadians who are severely disabled are employed, according to Statistics Canada, and that means scraping by to survive. According to the government’s 2021 report on MAiD, there were 179 people who ended their lives through the program who required but did not receive disability support.

Even more alarming is that there were 1,968 people who may have also required disability but didn’t receive it; their status was simply marked unknown. That would mean that approximately 25 percent of those who ended their lives through MAiD lacked disability support they needed.

Even when they do receive such support, it’s usually woefully inadequate. Global News reports on the case of Joannie Cowie, a 52-year-old resident of Windsor, Ontario who has COPD and Guillain-Barré syndrome and has dealt with cancer, as well as other physical ailments. But just as stressful is the never ending struggle to make ends meet:

Today, Cowie is unable to work, and has no family support. She lives with her daughter, a university student who is also disabled. Together, they must find a way to scrape by on $1,228 from Ontario’s disability support program, and a few hundred more for her daughter. It isn’t nearly enough

According to the AP, no province or territory provides a disability benefit income above the poverty line. And Heidi Janz, an assistant adjunct professor in Disability Ethics at the University of Alberta, told the AP that “a person with disabilities in Canada has to jump through so many hoops to get support that it can often be enough to tip the scales” and lead them to euthanasia.

Canada: A St. Catharines man says he will choose medically assisted death over homelessness. CityNews explores the ethics of MAiD amid concerns some feel they have no other choice.

Source: CityNews (Youtube) pic.twitter.com/GhQuOTRQA2— Wittgenstein (@backtolife_2023) November 12, 2022

There is also the fact that many mentally ill Canadians are not even on disability. According to the Toronto Star, 1 in 5 Canadians “either did not have prescription drug insurance or had inadequate insurance to cover their medication needs” and 1 in 4 “Canadian households were having difficulty finding money to buy their medicines”. Wait times for therapy can also be incredibly long, taking between 1 to 4 months to access counselling. According to Nouvelle News:

Those living with serious mental health illnesses disproportionately live in poverty. 1 in 5 Canadians will struggle with a mental illness in a given year, and 45% of those who are homeless either have a mental illness or disability in Canada. 35% of those on the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) have a diagnosed mental illness. In 2014, 23% of Canadians classified as disabled were low income and, according to the Homeless Hub, “people living with disabilities, both mental and physical, are twice as likely to live below the poverty line”.

Dr. Dosani, a palliative care physician and Assistant Professor in the Department of Family & Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, told Global News that such poverty and stress makes people sicker and is causing Canadians with disabilities to consider ending their lives:

The numbers are grim. Looking across the country, provincial disability support rates vary from a low of $705 per month in New Brunswick, to a high of $1,685 in Alberta. Try getting by on $1,228 per month in Toronto, or $1,358 in Vancouver, where the average rent on a one-bedroom apartment is about $2,500.

The result is that according to a 2017 report from Statistics Canada, nearly a quarter of disabled people are living in poverty. That’s roughly 1.5 million people, or a city about the population of Montreal.

“When people are living in such a situation where they’re structurally placed in poverty, is medical assistance in dying really a choice or is it coercion? That’s the question we need to ask ourselves,” Dr. Dosani says.

The answers, so far, are not pretty.

There’s the case of a Canadian veteran who was seeking help for PTSD and a traumatic brain injury and was offered MAiD by a Veterans Affairs employee.

There’s this case from Nouvelle News:

Recently, a Toronto woman named Sophia, with multiple chemical sensitivities (a disability), partook in MAiD. Sophia attributed this in part to her miserable living environment, saying it contributed to her condition. After 2-years of fighting for assistance from “all levels of government” to help in improving her living conditions. Peris, a worker from an organisation who assists people with multiple chemical sensitivities and who interacted with Sophia, stated that “it’s not that she didn’t want to live – she couldn’t live that way”

The UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities reported that in 2019 seniors told her they were offered a choice “between a nursing home and medical assistance in dying.”

According to the AP, a 61-year-old Canadian was hospitalized in June 2019 over fears he might be suicidal:

Within a month, Nichols submitted a request to be euthanized and he was killed, despite concerns raised by his family and a nurse practitioner. His application for euthanasia listed only one health condition as the reason for his request to die: hearing loss.

Assisted death is available in eight US states and the District of Columbia but is much stricter with requirements that the individual is terminally ill with a prognosis of six months or less to live.

It’s hard to tell if Canada will begin to get any MAiD tourism as the country’s info page only states that, “generally, visitors to Canada are not eligible for medical assistance in dying.”

Euthanasia is legal in Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Spain, plus several states in Australia. But Canada’s rules make it much more accessible than elsewhere. From the Associated Press:

— Unlike Belgium and the Netherlands, where euthanasia has been legal for two decades, Canada doesn’t have monthly commissions to review potentially troubling cases, although it does publish yearly reports of euthanasia trends.

— Canada is the only country that allows nurse practitioners, not just doctors, to end patients’ lives. Medical authorities in its two largest provinces, Ontario and Quebec, explicitly instruct doctors not to indicate on death certificates if people died from euthanasia.

— Belgian doctors are advised to avoid mentioning euthanasia to patients since it could be misinterpreted as medical advice. The Australian state of Victoria forbids doctors from raising euthanasia with patients. There are no such restrictions in Canada. The association of Canadian health professionals who provide euthanasia tells physicians and nurses to inform patients if they might qualify to be killed, as one of their possible “clinical care options.”

— Canadian patients are not required to have exhausted all treatment alternatives before seeking euthanasia, as is the case in Belgium and the Netherlands.

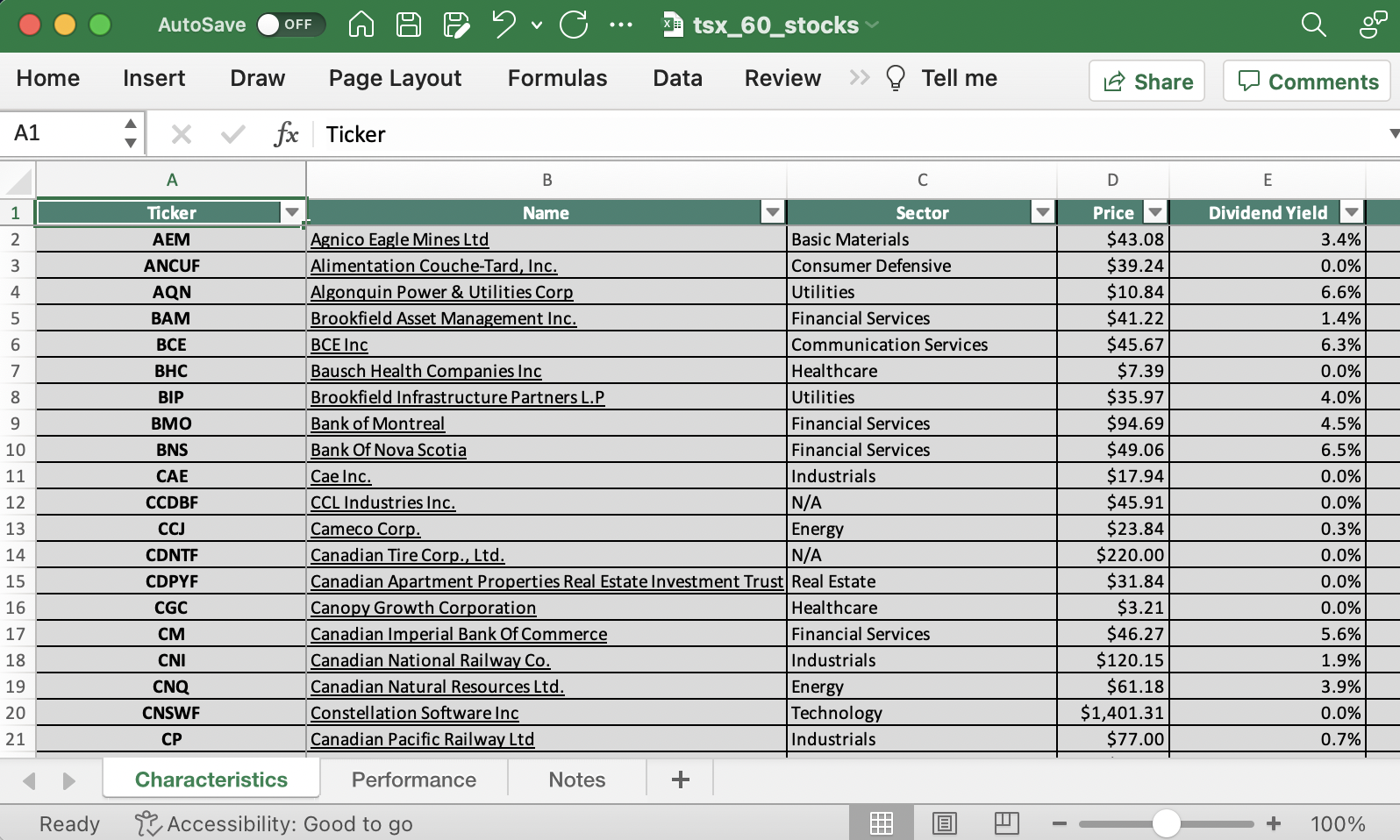

The number of people using MAiD has steadily grown since it was instituted in 2016.

According to the government’s 2021 report on MAiD, these were reasons people gave for ending their lives through the program:

- Loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities: 86.3%

- Loss of ability to perform activities of daily living: 83.4%

- Inadequate control of pain (or concern): 57.6%

- Loss of dignity: 54.3%

- Inadequate control of symptoms other than pain (or concern): 46.0%

- Perceived burden on family, friends or caregivers: 35.7%

- Loss of control of bodily functions: 33.8%

- Isolation or loneliness: 17.3%

- Emotional distress / anxiety / fear / existential suffering: 3.0%

- No / poor / loss of quality of life: 2.8%

- Loss of control / autonomy / independence: 1.7%

- Other: 0.7%

A Canadian Medical Association Journal report from 2017 detailed how MAiD could reduce annual health-care spending across the country by between $34.7 million and $136.8 million. They’re not there yet; a 2020 report from Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office estimated savings at $87 million – a fraction of Canada’s $264 billion healthcare costs that year.

I’ve been unable to find any estimates on savings in social safety net programs, such as for the Canada Pension Plan, which administers the country’s disability benefit. But even if all 10,064 individuals who ended their lives through MAiD in 2021 were on disability and receiving the maximum monthly payment of $1,685 in Alberta, that’s $203 million out of $4.6 billion in disability payments.

It is strange that despite urgings from numerous concerned groups across Canada, such as the Canadian Mental Health Association, more protective measures haven’t been put in place.

I feel like if MAiD were to continue some protections need to be put in place being like

1. Can this person find affordable housing

2. Can this person afford for and pay their bills/medications

3. Does this person have a support system that isn’t actively pushing this— Quinn (@Quinns_quirks) December 9, 2022

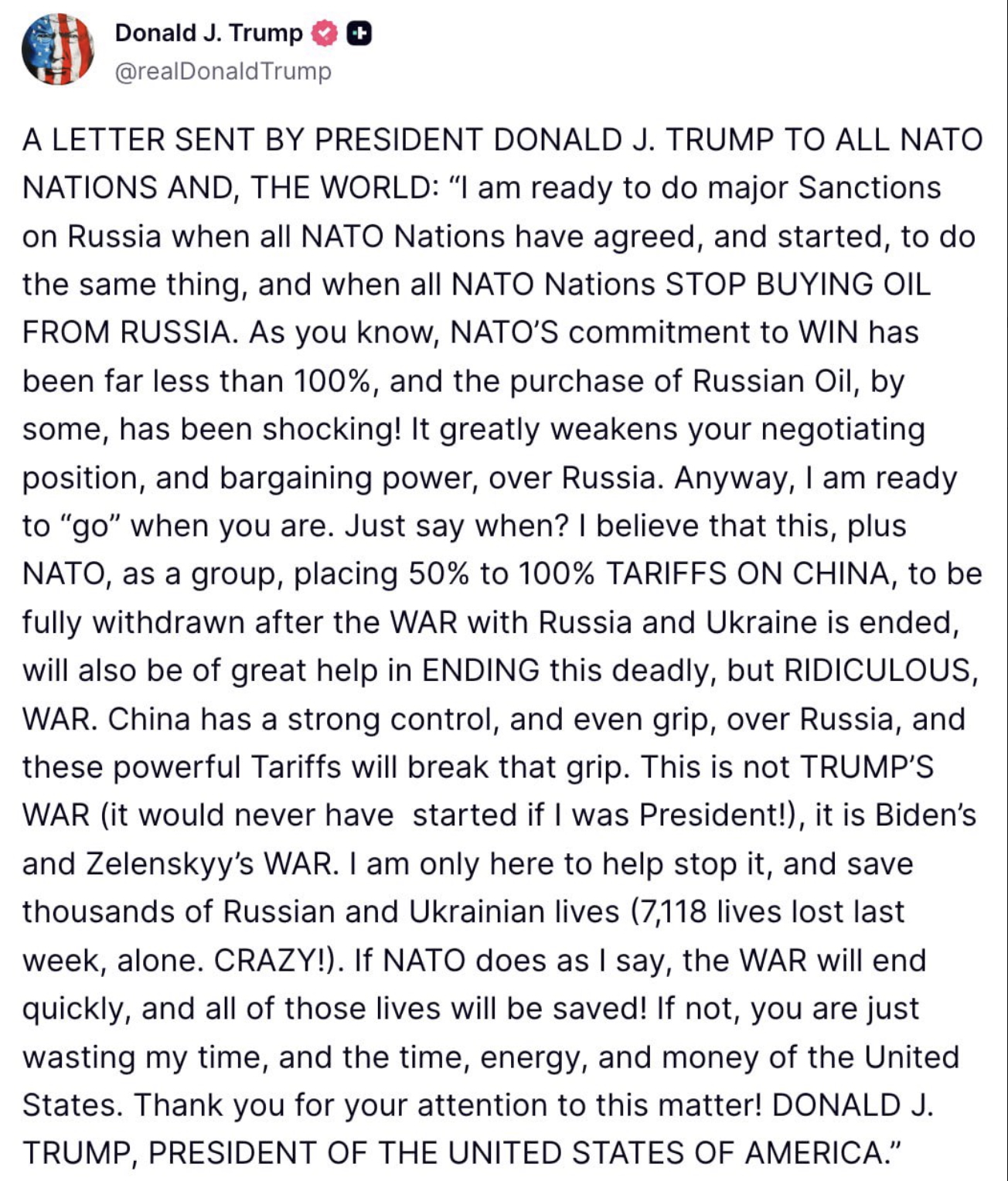

But if one remembers the rules of neoliberalism it begins to make more sense. Demonstrated here by the Associated Press:

Roger Foley, who has a degenerative brain disorder and is hospitalized in London, Ontario, was so alarmed by staffers mentioning euthanasia that he began secretly recording some of their conversations.

In one recording obtained by the AP, the hospital’s director of ethics told Foley that for him to remain in the hospital, it would cost “north of $1,500 a day.” Foley replied that mentioning fees felt like coercion and asked what plan there was for his long-term care.

“Roger, this is not my show,” the ethicist responded. “My piece of this was to talk to you, (to see) if you had an interest in assisted dying.”

Foley said he had never previously mentioned euthanasia. The hospital says there is no prohibition on staff raising the issue.

Let’s be honest, Canada and other countries have /been/ executing their poor; they’ve just never been so brazen about it.

— tenrec77 (@tenrec77) November 15, 2022

Take the following case of Les Landry who used to work as a truck driver before he developed a hernia, and his health went downhill from there. It’s a similar story to many a worker in the US, but while here they’d be left to turn to fentanyl, die on the street, or maybe thrown in jail for the crime of being homeless, in Canada the state will show them mercy.

Again from the Global News:

Today, the Medicine Hat, Alta., man is in a wheelchair and has severe chronic pain. But that’s not why he’s planning to apply for MAiD.

“The numbers I crunch … I will not make it. Like in my case, the problem is not really the disability, it is the poverty. It’s the quality of life,” he says.

Landry got by for years — just barely — on disability payments of $1,685 and timely donations solicited on Twitter. He also received a few extra benefits available under Alberta’s disability program — only a few hundred dollars extra, but it allowed him to budget and get ahead on his bills. Then, he turned 65, and through a bureaucratic loophole, actually lost benefits.

“What I lost is the disability benefits — service dog allowance, special diet allowance, transportation allowance,” he says. “I am no longer a person with a disability. I’m a senior citizen in poverty.”

He worries that with the loss of income and rising prices, he may soon be homeless. He’s making plans to end his life before that happens. …

“I don’t want to die. I don’t want to die. I just can’t see me living like this for the rest of my life.”