[ad_1]

Sundry Photography/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

Investment Thesis

Most large banks are riskier than they appear, despite regulators and politicians who promise to stabilize a system that crashes with the regularity of a Swiss watch. I generally steer clear of the sector.

Schwab (NYSE:SCHW) is indeed a large bank, but on a different mission and with other priorities. The assets on the balance sheet are boring, plain vanilla, which can be held to maturity. While there is pressure on current earnings from “cash sorting” depositors, this has been transparently acknowledged by management for months now. There is also evidence that Schwab and other large institutions are attracting new deposits from accounts fleeing smaller banks.

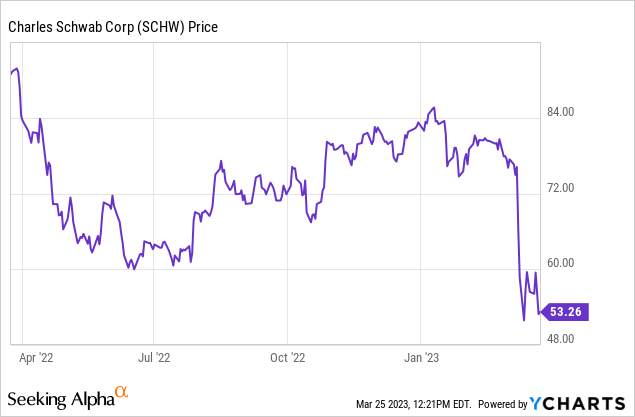

My purchase of the stock and selling of covered calls on the position reflects my opinion that the pullback in SCHW shares is overdone but will also take some time to recover. A significant contagion risk does not exist in Charles Schwab’s banking operations, but a more widespread market correction could impact its brokerage business.

Banks Are Fragile

Banks have historically been led by very conservative-looking management at the top ranks, with possibly more down-to-earth tellers with great smiles greeting depositors. Behind the scenes are mainly opaque balance sheets, sometimes obscuring exotic derivatives, often vetted by Nobel-winning economists, that generate fees and income and ticking time bombs.

I consider the term “banking” to be misleading as it refers to various activities, from providing an alternative to mattresses and cookie jars to creating and selling instruments that require hundreds of pages to document because they are so complicated.

Even the simplest form of banking requires the collective confidence of its customers to function. The fractional-reserve banking system concept boils down to this: for every dollar a bank receives in customer deposits, it holds only a fraction in “liquid” reserves to meet regular withdrawals. The remaining funds are then lent to borrowers based on the bank’s assessment of the riskiness of the loans. Depositors earn interest priced on the short-term nature of demand deposits, and borrowers pay a higher rate to reflect default risk and the longer duration of their loans. The bank earns the difference between the interest it charges borrowers and the interest it pays depositors. In a capitalist society such as ours, this system accelerates the economy by moving the capital from savers to income-producing assets faster than those assets produce income. In short, it leverages capital.

What about the fraction of deposits held in liquid reserves? Such liquid funds should be short-term and not subject to price fluctuation. In other words, under the bank’s mattress or in its cookie jar, presumably in a more secure location than my house. Cash and U.S. Treasury bills come to mind. Realize that the fraction of deposits in such liquid reserves to meet potential redemptions is based on regulatory requirements and expected or forecasted needs.

The reality is that this system is subject to the cyclicality of the economy. In a downturn, savings decline, causing deposits to dwindle. At the same time, loan defaults may increase as the leveraged assets do not produce the expected income. So the bottom line is that even a “simple” banking model is subject to risk and that this risk stems from making predictions of the future returns from the loan-funded assets and the stability of the demand deposits which fund those loans.

What makes this system even more fragile is the incentives inherent in the system. Competition among banks for depositors leads new entrants to offer higher rates to depositors and extend riskier loans to borrowers. And that is only for traditional banking operations. As mentioned, the most prominent “banks” go far beyond that simple lending model to create exotic products and derivative securities to generate fee income that often does not even serve the client’s interest. I plan to expand on this area in other articles, but for the scope of my thesis on SCHW, it is tangential.

For this article, the takeaway here should be that even ordinary bank operations are subject to cyclicality. The risk of a “run on the bank” always exists in fractional banking despite the many past crises and resulting regulations.

So Why Buy Charles Schwab?

SCHW has been caught up in the overall downdraft in the valuation of financial companies across the spectrum.

Before the most recent banking crisis ignited by the collapse of SVB, Schwab was already grappling with challenges such as regulatory changes to “payment for order flow” rules and “cash sorting” customers moving deposits to higher-yielding money market funds. Despite these headwinds, the market rewarded the company with higher valuations as it grew and attracted more clients and assets.

As a broker-dealer, SCHW is not primarily a bank, even though it is classified and regulated as one. As discussed above, I do not hold individual regular banks in very high regard, even though I acknowledge that the banking system is vital to the functioning of our economy. Unlike traditional banks, Schwab only invests a small portion of its excess reserves in commercial and real estate loans, as this is not the company’s main line of business. Instead, 85% of SCHW’s assets are in high-quality government and agency securities.

Ironically, these assets have also been scrutinized recently as the focus on bank portfolios has turned to unrealized losses in held-to-maturity investments. With over 80% of Schwab Bank’s deposits fully FDIC insured and 95% of the approximately $7.4 Trillion of AUM at Schwab in segregated custodial broker-dealer accounts, there is little reason to believe there would be a “run on the bank” occurrence. Therefore, there is also very little chance that any of the investments would have to be sold and the unrealized losses become realized.

This is an important point. The deposits at Schwab are there to facilitate customer trading and investing activity, not to act as a primary checking account. So whereas “cash sorting” does pressure one source of SCHW’s earnings, the funds are not leaving the firm. The company has reported net inflows since the crisis began. With over $7 Trillion in client assets, I am confident Schwab will find ways to make money serving those customers.

My Trade

I woke up this past Friday to the news that credit default swaps on Deutsche Bank (DB) were rising, pressuring its share price and those of U.S. banks. And this spilled over again to SCHW shares, despite not being an interconnected multinational financial center. True, any event that further strains the economy and financial markets risks also affecting Schwab’s brokerage activity. It is also possible that, like other large institutions, the company might continue to attract net new assets from smaller, less well-capitalized banks and ultimately benefit.

That said, I purchased SCHW shares in the pre-market (another thing I rarely do) at an average price of $51.80. During regular market hours, the stock recovered its intraday losses, trading up to $54 and change. I then wrote (sold) April 21’23 $60 Calls against my holdings, collecting a net premium of $1.67 per share. This made my effective net cost $50.13, with the possibility of the stock being called away for a 28-day return of 19.7%. As with all my covered calls, I will monitor events leading up to the expiration to decide whether to roll the options to a further date, repurchase them, or let the position go.

[ad_2]

Source link